Partition Voices: Untold British Stories

A review of Partition Voices: Untold British Stories by Kavita Puri

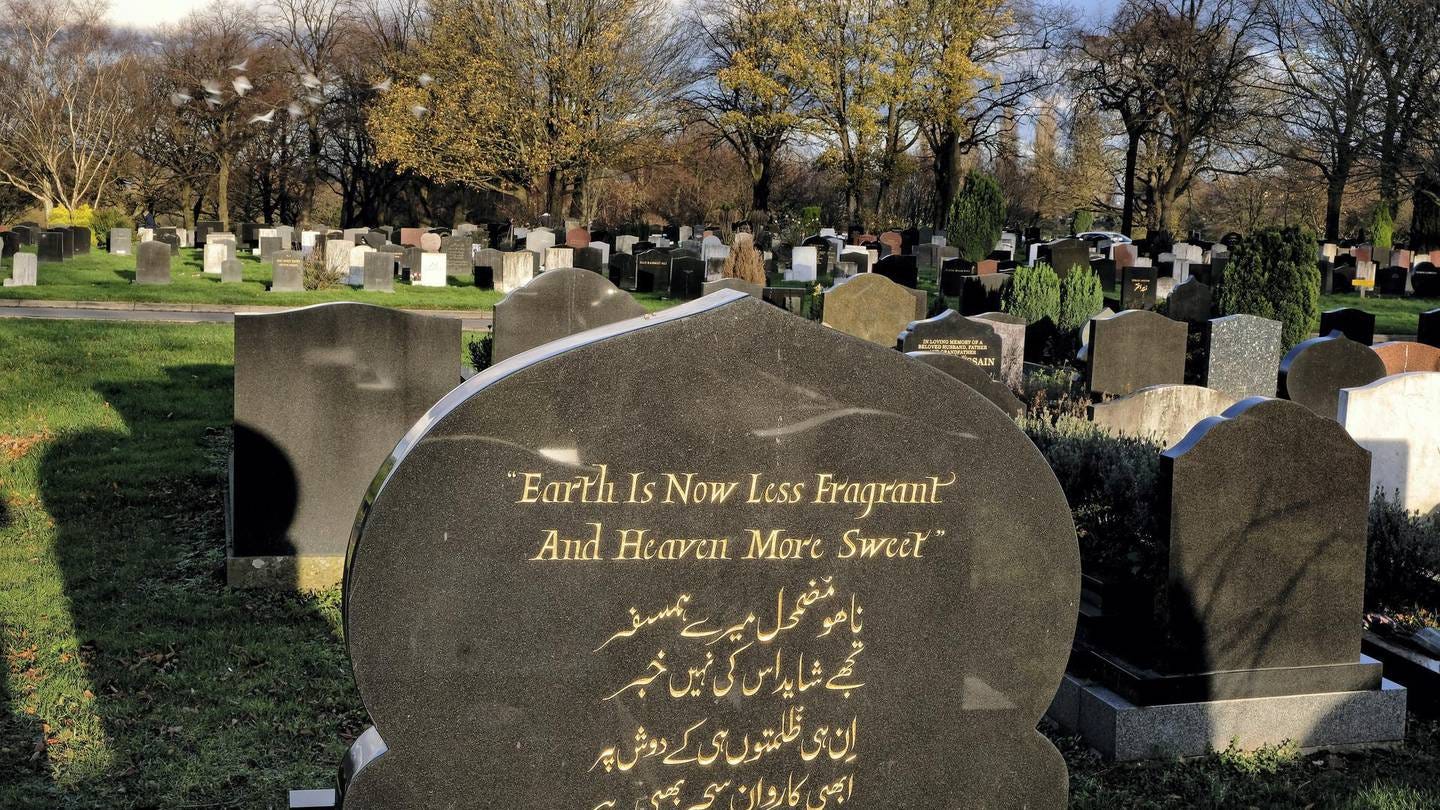

“It was a great tragedy and we didn’t like being friends one day and enemies the next… we will always curse the authorities, the British or Indians, the politicians who made this mess. I will never forget these tragic events. Always remember. I will take these things to my grave.”

One of my reading goals this year is to read more literature pertaining to South Asia, particularly around the 1947 partition. Aside from family stories, documentaries and academic texts, Partition Voices: Untold British Stories is the first book I’ve picked up on the topic that centres the experiences of British South Asians that witnessed the horrors of partition, as well as Anglo-Indians that once lived in the land during the British Raj. The latter are seldom mentioned in discussions around partition, partially due to the prioritisation and urgency of preserving the first-hand accounts of South Asian elders, and partially due to the lack of individuals left alive to provide their stories of their lives under the Raj.

Published in 2019, Partition Voices came about following the BBC Radio 4 documentary of the same name by journalist Kavita Puri two years prior. This work contains a series of short interviews with men and women residing in Britain. By and large, interviewees whose families were forced to flee during the partition did not realise the extent of their displacement. In fact, before leaving, some handed their house keys over to neighbours for safekeeping until their return. Most, as we know, never stepped foot in their homes again.

The purpose of Puri’s work is not to provide the reader with a full historical or political account of the lead up to partition, though it is useful that she provides a succinct contextual recap of British presence in India and the subsequent independence groups that were formed on the basis of religion. To get the most out of this work, and to be able to fully appreciate the stories of the individuals interviewed, it would be useful to familiarise yourself with the history of the land.

Of the twenty interviews that make up this book, the majority of volunteers (15) were men (5 Hindu, 4 Sikh, 3 Muslim, 2 English, 1 Parsi) and 5 were women (1 Hindu, 1 Sikh, 2 Muslim, 1 English).

Discussing partition often brings back traumatic flashbacks of bloodshed, kidnapping and violence for those that survived and lived to tell their tales. Interviewees such as Bashir remember the harmony that was once fostered in villages between people of different faiths prior to partition, before and during the British Raj.

“Eventually, the movement of Bashir’s Hindu and Sikh neighbours started. He watched them move out peacefully. ‘We were sad, they were sad that they were leaving. I remember when the [Indian] army trucks came and they ordered them in there with the little belongings that they could take and we were embracing each other, crying.’”

This touching account of solidarity lies in stark contrast to the animosity that was amplified post-partition and still persists today. Hatred, intolerance and anger replaced camaraderie and unity for many. Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs and other minorities hailing from the same background and culture were able to look past their religious differences and coexist with their neighbours without any real major issues.

“Sawan remembers saying goodbye to his Muslim ‘brothers’ in the middle of the night. He can still recall the sadness he felt at their leaving. ‘We were very disturbed, we had all been living together for hundreds of years.’”

Some accounts are more harrowing, highlighting the senseless violence that persisted even after most had fled to their respective independent states. One interviewee recalls how his elderly mother was targeted and almost burned alive in her house by neighbours with whom they had lived peacefully for decades.

“How was it possible for people who once coexisted so peacefully together to murder each other, and so viciously?”

The interview that moved me the most was My Faith in Humanity is Shaken, the story of Gurbakhsh Garcha, a man from Dhandari Khurd, a small, then largely-Sikh village in Punjab. Gurbakhsh’s story is interesting in that it captures both the spontaneity with which villagers turned against each other, despite their centuries-long coexistence and shared culture, as well as how they fiercely protected their fellow villagers that were of the religion that was to be expelled.

“‘We want to kill Muslims,’ they shouted back. “They are my children,’ Gurbakhsh’s grandfather told them. “They have been working with me since they were little boys. You will have to kill me before you touch them. If you touch me, the whole village will be here and you won’t escape.”

Within this story, the part that I found the most distressing was:

“The grandfather noticed that the groundnut crop grew surprisingly lushly in certain, seemingly random, patches of the field. They discovered that the crops had been fertilised by human bodies, refugees who had died on their journey - the sick, the elderly, the young - buried in shallow graves. His grandfather told Gurbakhsh not to disturb them. ‘It is their place of rest’, he said.”

In terms of the accounts of women, the interview with Khurshid Begum in She Took a Stand was particularly interesting. Despite initiatives at the time to recover girls and women that were kidnapped and assaulted by men, many were never reunited with their families or children again. Tragically, for those that were reunited, they were not accepted by their families or were killed in the name of honour.

“It wasn’t only that they were raped and abducted… They had marks of the other religion tattooed and stamped on their bodies. Their breasts were cut off, all kinds of humiliations were heaped upon them. And it was just part of this whole thing of treating women like chattel.”

Partition Voices is an important work that illuminates a recent piece of history that many are unfamiliar with or do not know much about. A South Asian Muslim, Hindu or Sikh, will largely only be familiar with the stories and tragedies of their own people, and so it’s interesting (and devastating) to hear stories from individuals of different faiths, cultures and villages. I look forward to listening to the documentary (I probably should’ve listened to it before reading the book, but I have to return it to the library soon so wanted to finish it asap).

A breakdown of the interviews / interviewees is provided below:

End of Empire (author’s narrative)

The Days of the Raj - Englishwoman

Hurt the British! - Hindu man

I Became Convinced of the Muslim League - Muslim man

Fishing with Dead Bodies - Englishman

It Was Magic - Englishman

Partition (author’s narrative)

My Faith in Humanity is Shaken - Sikh man

Desh - Sikh man

My Mind is Still Confused - Sikh man

I Have Seen This - Sikh man

She Took a Stand - Muslim woman

The Good Old Days - Hindu man

You Had to Choose - Muslim man

Horrible Days - Parsee man

India was Mine as Well - Muslim man

They Become like Animals - Muslim woman

Mother, I Have Come Home - Hindu man

Legacy (author’s narrative)

Rootless - Sikh woman

We Should Talk - Hindu woman

Silence - Hindu man

My Father - Hindu man